By Sharon Lurye Aug 26, 2021

This year’s housing boom has presented a financial windfall to sellers and an agonizing ordeal to buyers. However, even homeowners who stayed put may be affected—by being hit with higher property taxes.

Average property taxes paid rose 4% in 2020, according to data from real estate information firm ATTOM Data Solutions. Housing experts expect them to jump even higher in 2021 as many communities that lost revenue during the COVID-19 pandemic are scrambling to raise new funding. Rising home prices may allow them to cash in going forward.

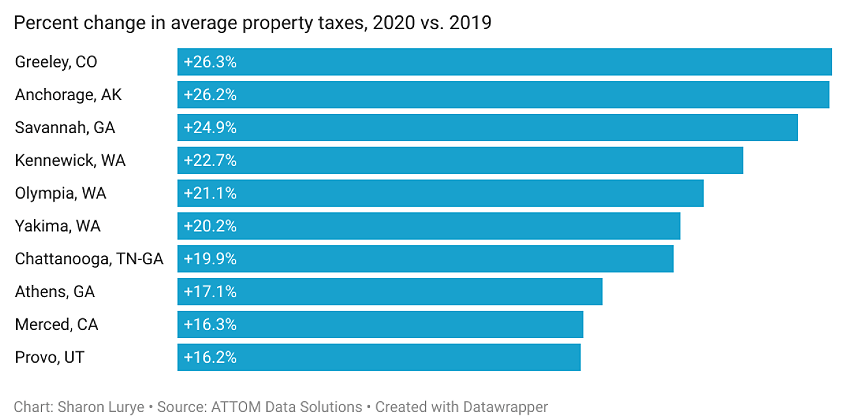

Metropolitan areas in Alaska, Colorado, Washington, Georgia, and California saw some of the highest price shocks. In Anchorage, AK, for example, average property taxes rose by $987.65, or 26.2%, in one year, according to ATTOM.

“It’s going to bite deep into both homeowners’ and landlords’ pocketbooks, as reassessments kick in and send property tax bills soaring,” says Brian Davis of Spark Rental, a firm that makes software for landlords.

Property taxes are expected to increase by about 6.5% in 2021, according to realAppeal, a company that helps homeowners appeal property tax bills. This larger financial burden will have the hardest impact on homeowners who lost their jobs during the pandemic, elderly residents living on a fixed income, and those struggling to get by in the face of rising inflation. Even tenants will pay the price, as at least a portion of those tax increases are expected to be passed down to them in the form of higher rents.

Average property taxes are lowest in the South, with Alabama coming in cheapest at an average of $841 a year paid in 2020, according to ATTOM. The highest are in the Northeast, California, and Texas, with New Jersey topping the list with a whopping average tax bill of $9,196. Taxes can be even higher in particular areas, such as Westchester County, where annual property taxes can easily top $24,000.

“Many of our clients who are older and living off of Social Security or pensions are beginning to wonder whether or not they’ll be able to remain in their homes as their property tax bills continue to rise,” says Frank DiZenzo, chief revenue officer of realAppeal.

However, higher taxes are not expected to hit all parts of the country equally—or all at the same time. Property taxes usually get collected by local jurisdictions (e.g., counties, cities, towns, school districts, or special districts like water authorities) to help pay for a myriad of services, from the fire department to police to the library. These jurisdictions follow different schedules for when they reassess home values and update tax bills.

Moreover, many states and counties offer ways to ease that tax burden, whether through property tax exemptions or relief programs for veterans, disabled people, or senior citizens.

“We’ve met thousands of property owners that aren’t aware these benefits exist, and as a result leave thousands of dollars on the table every year,” says DiZenzo.

Where property taxes are rising and why

The main reason that taxes rose in 2020, and are likely to rise again in 2021, is the soaring housing market.

Median home list prices shot up about 7.2% year over year in 2020 and are estimated to rise roughly 11% in 2021 compared with the previous year, according to Realtor.com® data. White-collar workers and urbanites flocked to larger houses in the suburbs during the pandemic.

Property taxes are usually calculated as a percentage of a home’s taxable value. When home prices go up, local government has a larger tax base, leading to higher bills for homeowners.

But first, the local tax assessor has to update estimates about how much each home in the area is worth.

As a result, says Spark Rental’s Davis, 2020’s housing boom “will take a couple years to fully translate into dramatically higher property tax bills, because counties usually reassess property values every few years, often three-year intervals.”

The 10 Metros with the Highest Property Tax Growth

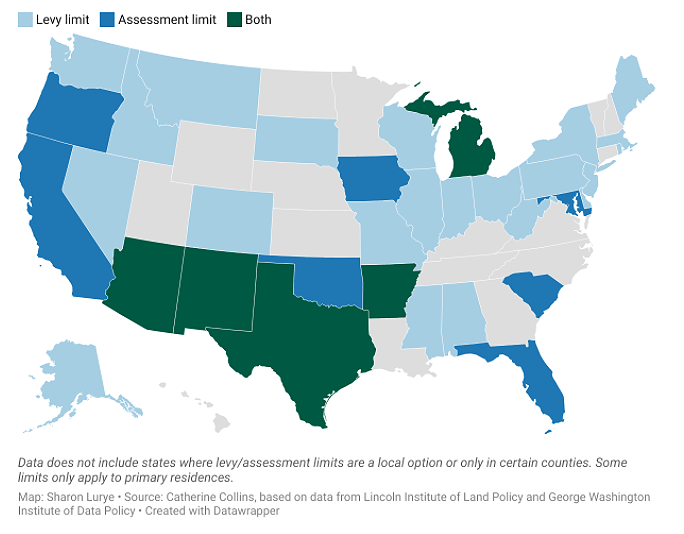

In addition, 34 states have laws on the books that restrict how much taxes can grow in a single year. Some of these are restrictions on tax levies, meaning the government can’t collect more than a certain amount of revenue. Other states have restrictions on assessments, meaning there’s a limit on how much the taxable value of your home, and thus your tax bill, can go up in a year.

Watch: Chief Economist’s View: The Latest Housing Data Trends

“States have put in place two types of limits to mitigate these increases: levy limits that restrict the amount taxes can increase, and assessment limits that restrict the growth in the value that is taxable,” says Catherine Collins, senior research associate at the George Washington Institute of Public Policy, a research institute at George Washington University in Washington, DC.

These limitations make it hard to predict exactly which states will see the highest property tax bumps in the years to come.

“There is no straightforward answer as to what is going to happen to homeowners’ taxes in the post-pandemic world,” says Collins.

34 States Put Some Limits on Property Tax Growth

Twenty-two states put limits on the growth in tax levies, seven states have limits on tax assessments, and five states have both.

In California, for example, assessed home values, which affect how much homeowners are taxed, cannot grow more than 2% in a year until the home is sold. Florida limits the growth in home value for primary residences to 3% per year, while Texas limits it to 10%.

Property taxes could rise more substantially going forward

While a more than 4% property tax increase last year may sound like a lot, it has the potential to go even higher. Home values are often reassessed by local governments, and taxes go up or down accordingly.

Tax rates may also change as pandemic-related expenses and budget shortfalls put pressure on some localities to increase their tax rates in the coming year. In Seattle, for example, residents saw their average tax bill go up by $633 from 2020 to 2021 as county officials bumped up the tax rate.

“In addition to increases in home values and their assessments, we’re seeing many county tax jurisdictions increase their property tax rates as well, to bolster their revenues after suffering from reduced collections from other sources,” realAppeal’s DiZenzo says.

While residential properties have increased in value due to the lack of available housing, commercial properties took a hit during the pandemic as workers abandoned office buildings and consumers stayed away from shops and restaurants. Local governments may have to lean more on residential taxes to make up for the loss of commercial revenue.

“The homeowner is going to pay more because the Starbucks is paying less,” says Collins of the George Washington Institute.

Take Pittsburgh. In the city, about 150 office buildings downtown make up around a third of the property tax base, says Robert Strauss, a professor of economics public policy at Carnegie Mellon University. What happens if those buildings sit empty?

“If they’re only 80% occupied, that creates financial problems for the communities,” says Strauss. “They have to ask themselves, do they want to go after the homeowners? … The money’s got to come from somewhere.”

The Urban Institute, a DC-based think tank that carries out economic and social policy research, found that 36 states saw total tax revenue fall between March and August 2020, which could in turn put pressure on local governments.

However, the picture was not entirely bleak: Eight states actually saw a growth in total revenue. (Data was unavailable for the rest of the states.) In addition, 12 states reported higher income tax revenue. This trend may be because the people who earn enough to pay an income tax in the first place are more likely to have a steady, white-collar job that can be done remotely.

What can homeowners do to fight property tax increases?

This unpredictability in the economy, combined with byzantine tax laws, can make it hard for homeowners to really know whether their taxes will go up or down in the coming years.

“Everyone thinks that property taxes are simple and ho-hum, but for homeowners, it’s one of the hardest ones to understand,” says research associate Collins.

What homeowners can find out for sure is whether they are eligible for a break in their property taxes, known as a homestead exemption. It lowers taxes for homeowners as long as they actually live in the property. It does this by reducing the taxable value of the house. This means even if the house could sell on the market for a certain price, it’s taxed like a house valued at a lower price. Forty-six states, plus Washington, DC, have some kind of homestead exemption, according to the Tax Policy Center at the Urban Institute and Brookings Institution.

“You may qualify for benefits that will help keep your property tax bill manageable by reducing the taxable value of your home, reducing your tax rate, or ‘locking in’ the taxable value of your property so that it cannot increase in future years,” says DiZenzo.

In the state of Texas, homeowners can score a $25,000 homestead exemption. Disabled and elderly homeowners are eligible for an additional $10,000 exemption for school district taxes. Once they receive that exemption, school taxes remain frozen and cannot go up as long as the homeowner still lives in the home.

Meanwhile, in New York City, seniors who make less than $50,000 can have the taxable value of their home reduced by as much as 50%.

Homeowners across the country who believe their home is being assessed for more than the fair market rate can also appeal their tax bill.

“Taxpayers get mad,” says Carnegie Mellon’s Strauss. As a result, “it’s just a matter of self-interest and time as the homeowners, the people who bought houses, start litigating.”

Sharon Lurye is a freelance journalist based in New Orleans. She graduated from Columbia Journalism School in 2018.